Scientists discover how high-energy electrons strengthen magnetic fields

The research could lead to a better understanding of extreme astrophysical environments and the development of compact high-energy radiation sources for science.

More than 99% of the visible universe exists in a superheated state known as plasma – an ionized gas of electrons and ions. The motion of these charged particles produces magnetic fields that form an interstellar magnetic web. These magnetic fields are important for a wide range of processes, from the shaping of galaxies and the formation of stars to controlling the motion and acceleration of high-energy particles like cosmic rays – protons and electrons that zoom through the universe at nearly the speed of light.

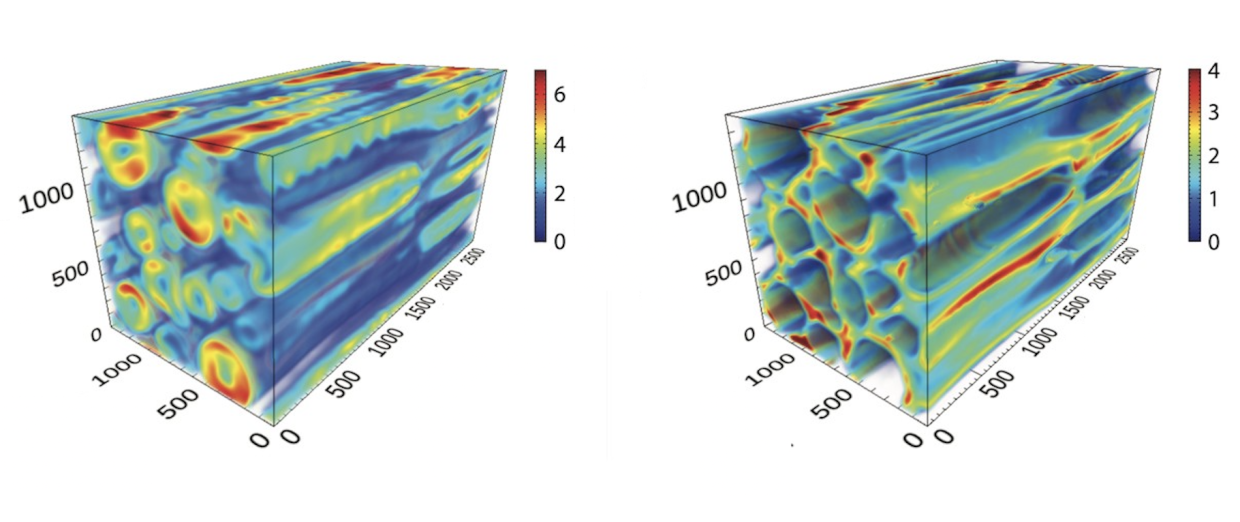

In previous research, scientists found that in regions where high-energy electrons are produced, magnetic fields are intensified. But until now, the way energetic particles affect magnetic fields was not well understood. In a paper published on the cover of Physical Review Letters in May, researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory show how electrons can amplify magnetic fields to much higher intensities than were previously known.

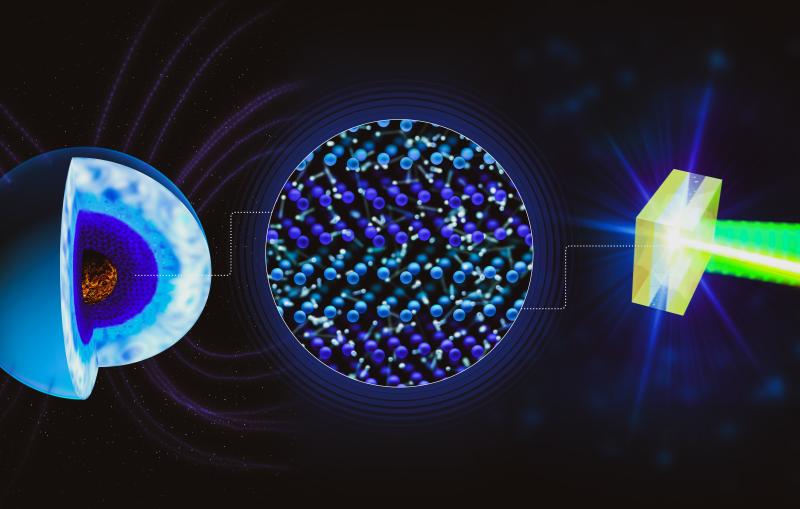

The motion of electrons carries an electrical current, which produces magnetic fields. Usually, charges from background plasma interfere with this current by moving in a way to cancel it, making strong magnetic fields difficult to produce. Using numerical simulations and theoretical models, the researchers found that high-energy electrons can actually expel the background plasma to create a hole, making it harder for the plasma to cancel their current.

“As the current is exposed, strong magnetic fields are produced that further push the background plasma away, creating bigger holes, leaving more of the current exposed, and producing even stronger magnetic fields,” says Ryan Peterson, a PhD student at Stanford University and SLAC who is the first author of the publication. “Eventually, these magnetic fields become so strong that they bend the electrons and slow them down.”

This process could potentially be at play in the brightest and most energetic electromagnetic events in the universe: extreme explosions known as gamma ray bursts. Observations suggest that magnetic fields must be significantly amplified by energetic particles to produce the observed radiation but, until now, the way the field is intensified has been a mystery.

“Every time a new fundamental process is identified, it can have important consequences and applications in different areas of research,” says Frederico Fiuza, a scientist who worked on this research and leads the high energy density science theory group at SLAC. “In this case, the amplification of magnetic field by high-energy electrons is known to be important not only for extreme astrophysical environments, such as the gamma-ray bursts, but also for laboratory applications based on electron beams.”

The researchers are currently working on new simulations to better understand the role that this process can play in gamma-ray bursts. They also hope to find ways to reproduce it in a laboratory experiment, which would be an important step in developing compact high-energy radiation sources. Those sources would allow scientists to take pictures of matter on the atomic scale with extremely high resolution for applications in medicine, biology and materials research.

This research was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.